Civil War anniversary: 1861: Spring into Summer … Peace into War

Published 1:32 am Sunday, June 5, 2011

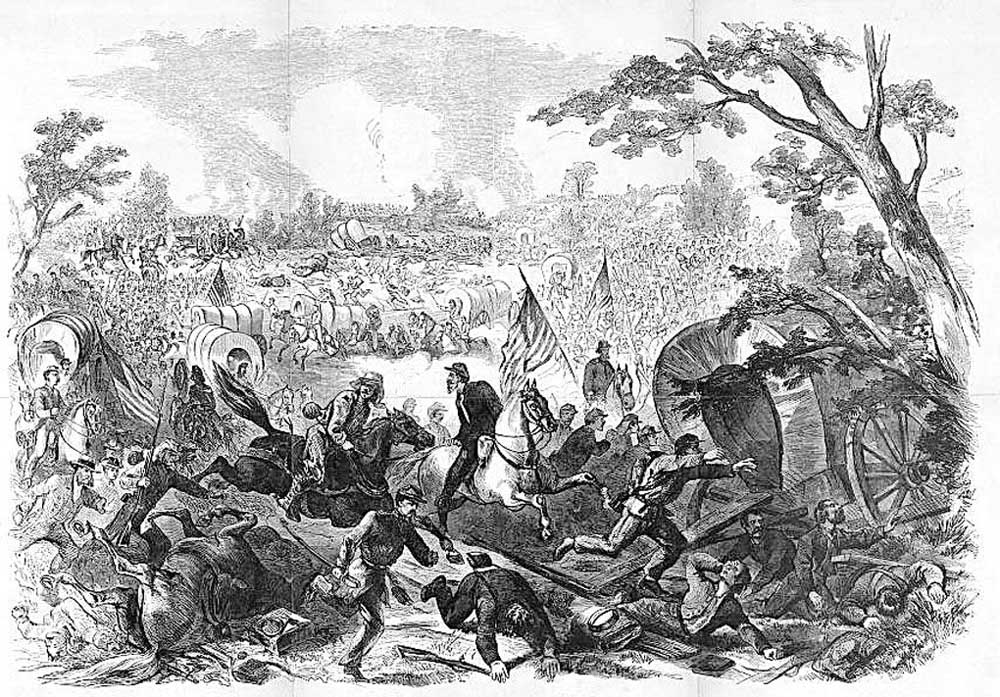

- SUN-1st Battle of Manassas (Bull Run)- Lib.of Congress (B and W).jpg

The conflict that had been brewing for decades between the Northern and Southern states finally reached a boiling point in April 1861 at Fort Sumter in the Charleston, S.C., Harbor.

Trending

Fort Sumter had long been a U.S. military stronghold, having been built following the War of 1812. Still under Federal control, recent events caused it be located on Confederate soil. The newly independent Confederacy felt it could not tolerate a foreign power in control of a fortification within its borders. Dialogues, negotiations, and communications continued to the last minute, but to no avail.

Confederates began bombarding the fort early Friday morning, April 12, and the garrison surrendered the following day. By Sunday the Confederate “Stars and Bars” replaced the United States flag. On Monday the New York Times reported, “The scene in [Charleston] . . . is indescribable; the people [are] perfectly wild . . . The bells have been chiming all day, guns firing, ladies waving handkerchiefs, people cheering, and citizens making themselves generally demonstrative.”

Fortunately, the action at Fort Sumter was brief, and resulted in no direct casualties on either side. Rumors quickly spread that the war was over. They would prove to be premature.

Feelings about the events at Fort Sumter were strong on both sides. In the North, many felt their country was dishonored; others called the Confederate attack treason. Many felt the liberty and independence for which their forefathers had fought were threatened. In the South, many believed the attack was entirely justified. It had been an act of self-defense, the retaking of its own soil by their new Confederate nation.

On Monday, April 15, President Lincoln called for a draft of 75,000 federal citizen-soldiers to serve for 90 days to put down the insurrection. Technically, it was not a declaration of war. (It would be July before the official Congressional resolution of war would be passed.) But to the Confederates, it might as well have been. In their view, their actions had been legal, not an “insurrection.” Soon thereafter, four more Southern states seceded and joined the Confederacy, making a total of 11.

State militias (citizen-soldier units, the forerunner of the National Guard) were called up in the Southern states, and men and boys who knew nothing of the bloody reality of battle began to drill and prepare for the fight. A veteran observed that it was akin to breaking “wild colts.”

Trending

The enlistment for Confederate soldiers was for 12 months: One year was considered adequate, as none of the leaders on either side, civilian or military, foresaw how long and terrible the war would be.

Throughout the months of spring, and into summer, the mood escalated almost uncontrollably toward confrontation. Bands played, banners waved, and orators shouted. Newspaper editors, politicians, military experts, the average man or woman on the street … everyone was abuzz with excitement about the latest news. Everyone had an opinion on states’ rights, nullification, state sovereignty, President Lincoln, Southern independence, the Confederacy, secession, abolition, the Union, slavery in the territories, the ethics of the various positions, and the intolerance of the other side.

Neither side understood the other’s motives or capabilities. Each side overrated its own resources and potentials, and underrated its adversary’s. A veteran remembered the times: “The South, proud and haughty, looked with disdain upon the courage of the North; considered the people cowardly, and not being familiar with firearms would be poor soldiers; that the rank and file of the North … would not remain loyal to the Union … and would not fight. … The North looked upon the South as a set of aristocratic blusterers … a nation of weaklings, who could not stand the fatigues and hardships of a campaign.”

Each side was confident it would prevail.

Emotions ran high, and fevers were pitched. Far from being clear-cut, splits developed on issues within families, within communities, and within states. Clergy, citizens, and soldiers on both sides appealed to the same God, and, deeming their own standpoint to be the right and just one, prayed for intervention, support, and blessing for their cause. Both sides at times claimed they favored states’ rights, but support for this concept was often selective: neither side wanted another state to have the power to sustain a position antagonistic to their best interests.

Some young soldiers had no firm opinions on the issues, yet contributed to the energy and excitement of the day. For some, no reason to fight was necessary. When asked by a Northerner why he was fighting, one rag-tag Virginia private who owned no slaves and had little interest in states’ rights answered, “I’m fighting because you are down here.”

Others were simply caught up in the thrill of the stampede, joining because friends and relatives had joined. Many, having never traveled outside their home counties, viewed the looming war as a golden opportunity for the travel and adventure of a lifetime.

The theater of conflict soon shifted to northeastern Virginia, where Southern soil was separated from Washington, D.C., only by the Potomac River. A shipyard in Norfolk, and an armory and arsenal at nearby Harpers Ferry, were valuable sites, the control of which both sides wanted. In addition, on May 20 the Confederate capital was moved from Montgomery, Ala., to Richmond, only 100 miles south of Washington. A 100,000 citizen-soldiers, from both North and South, converged on Northern Virginia, intent on settling the matter, once and for all.

Thousands of soldiers from Georgia made the trip to Virginia by rail. One from Columbus wrote, “At all the stations on the road, we were received with every demonstration of joy and enthusiasm. [At one station] the ladies met us at the depot, with water, cakes, flowers, ect. … Our company seem to enjoy themselves finely.”

Another, from Atlanta, wrote from Richmond, “We are now comfortably situated in a large and beautiful grove, with plenty of water and everything calculated to render the soldier healthy … We have dress parade every evening at 5 o’clock, and are visited very extensively by the patriotic ladies of Richmond. On yesterday I made several acquaintances among the ladies, and received several bouquets.”

While it was widely accepted that a showdown of some kind was inevitable, many believed that it would be short, possibly bloodless. An almost jovial spirit, a mood of anticipation and excitement, continued on both sides until the day of the first bloody battle. Crowds of sightseers, many from Washington — civilians, reporters, politicians, entertainment-chasers, and curiosity-seekers — gathered on the heights overlooking the battlefield at Manassas Plains to view the expected gala event. Some even brought picnic lunches. Ladies came dressed in their finest attire, anticipating a dance afterwards.

Early on Sunday morning, July 21, 1861, 60,000 men faced off along a deep, dark creek called Bull Run. Most were young, eager, and naïve. Most had never seen combat before. By the time the sun had set, they would have seen what war was really about — “seen the elephant,” in the slang of the day.

The day was long, hot, humid, and bloody. The South won a magnificent victory, and sent the Federal troops running back to Washington in a rout rarely matched in warfare. But it came at a terrible price.

What was left was a field of unspeakable carnage — dead and wounded, men and animals, baggage, wagons, artillery, guns, knapsacks, and caissons. Casualties numbered nearly 5,000, 2,000 Confederate and 3,000 Federal. Many of the wounded would suffer first, and die later. “It was a terrible, bloody battle,” wrote one soldier from Atlanta, “and I was in it. I have seen the horrors of war, in all its blood and terror.”

People on both sides, North and South, were stunned, shocked, and appalled. No one, on either side, had expected such a dreadful slaughter. Never before had there been such a massive engagement on the North American continent. Never before had an American army experienced such staggering losses.

Spring had turned into summer. Peace had turned into war. Suddenly, war was real.

This article is part of a series of stories about Dalton and life in Dalton during the Civil War. The stories run on Sunday and are provided by the Dalton-Whitfield Civil War 150th Anniversary Committee. To find out more about the committee go to www.dalton150th.com. If you have material that you would like to contribute for a future article please contact Robert Jenkins at 706-259-4626 or robert.jenkins@robertdjenkins.com.